Endoscopic treatment with fibrin glue of post-intubation tracheal laceration

Introduction

Post-intubation tracheal laceration (PITL) is a rare and potential life-threatening condition requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment. The overall incidence is 1/20.000 following elective endotracheal intubation but it increases three-fold in case of emergency endotracheal intubation (1). There are several risk factors for PITL due to (I) the patient’s condition: anatomical tracheal abnormalities, weakness of pars membranosa, underlying lung disease, advanced age, female; (II) operator’s experience: multiple forced intubations, incorrect position of the endotracheal tube, reposition of endotracheal tube with inflated cuff; (III) type of endotracheal tube: inappropriate size, double-lumen tube; and (IV) technique of intubation: using stylet, cuff over-inflation (1,2). In the most of cases, the PITS is caused by the tip of the endotracheal tube that tears the pars membranosa while advancing into the trachea. Clinical manifestations are subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, and pneumothorax associated with other clinical signs as dyspnoea, dysphonia, cough, and haemoptysis. In case of suspicion of PITL, high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan and flexible bronchoscopy should be both performed since the sensitivity of HRCT alone for diagnosing tracheal laceration is 85% (3,4). The management of PITL includes conservative treatment, surgical treatment, and endoscopic treatment. The choice is based on the patient’s clinical condition and on the characteristic of the PITL. Generally, a conservative treatment is indicated in patients with laceration <2 cm, having minimal and non-progressive symptoms and without air-leakage on spontaneous breathing while surgery is the treatment of choice for laceration >4 cm, or in presence of mediastinal collection or oesophageal injury, or rupture involving the carina and the main bronchus in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. The best management for rupture between 2–4 cm remains matter of debate. Some authors recommend surgery while others do not definitely exclude endoscopic treatment giving a greater attention to the depth of the tracheal injury than to its length (1-11). Recently, Cardillo et al. (12) classified PITL into four levels according to the depth of the tracheal fear and proposed a protocol for its management. Level I: laceration of mucosa and submucosa with subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema; Level II: tracheal lesion up to the muscularis wall without mediastinal emphysema and without oesophageal injury; Level III-A: complete laceration of the tracheal wall with oesophageal or mediastinal soft-tissue hernia without oesophageal injury or mediastinitis; and Level IIIB: any laceration of tracheal wall with oesophageal injury or mediastinitis. Level I and Level II should be managed non-surgically; Level III-A can be managed conservatively in tertiary centres due the high risk of complications; and Level III-B should be treated with surgery.

Herein, we reported our experience with the endoscopic closure of PITL with fibrin glue.

Patient selection and workup

The indications for the endoscopic closure with fibrin glue of PITS are:

- Subcutaneous emphysema, cough, and haemoptysis occurred after tracheal intubation suspect a tracheal laceration;

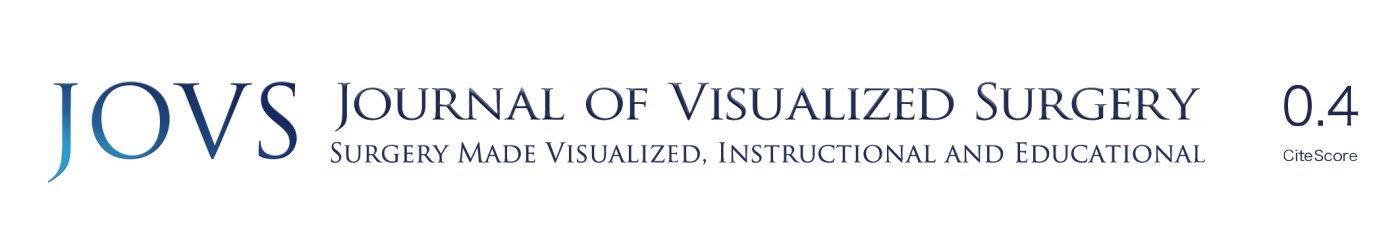

- HRCT scan of neck and chest reveals the presence of a tracheal lesion, pneumomediastinum and oesophageal bulging in absence of other signs as pneumothorax, mediastinal collection and oesophageal injury (Figure 1);

- The flexible bronchoscopy shows a laceration localized in the upper or middle trachea, ≤4 cm in length, with injury of mucosa and submucosa;

- Esophagram and Esophagoscopy confirm the lack of oesophagus injury;

- The presence of stable vital signs, an adequate respiratory status and standard preoperative examination including blood testing and electrocardiography ensure that the patient can tolerate the endoscopic procedure.

Preoperative preparation

The specific preoperative preparation for endoscopic repair of PITS is not different from that of the traditional flexible bronchoscopy.

- Lidocaine spray and 2% Lidocaine are used for the anaesthesia of the throat and of the vocal cords, respectively.

- Intravenous midazolam at a dose of 0.05 mg/kg in combination with a short-acting opioid (fentanyl or alfentanil) is administered 5 minutes before the procedure to obtain a moderate sedation.

Equipment preference

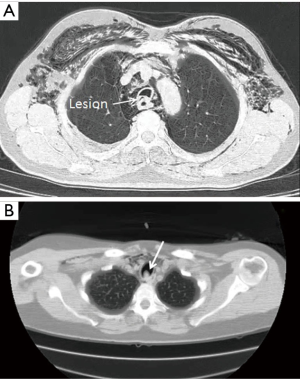

The whole procedure is performed in operating room using the following instruments (Figure 2):

- A video flexible bronchoscopy having a working channel >2 mm to allow the passage of the double lumen catheter for fibrin glue application;

- A face mask for non-invasive positive pressure ventilation and a plastic mouthpiece is inserted to protect the instrument from an inadvertent bite. All equipment for an emergent endotracheal intubation should be available in case of sudden desaturation;

- A commercially available preparation of fibrin glue (Tissucol®, Baxter AG, Vienna) where the two individual components (fibrinogen and thrombin) are heated in heating units for up to 20 minutes before their use;

- A dedicated double lumen catheter (Duplocath® 180, Baxter AG, Vienna) with a length of 180 cm and a diameter of 0.17 cm to instill simultaneously into the laceration the two components of fibrin glue.

Procedure

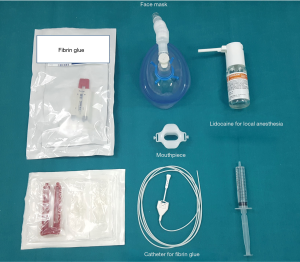

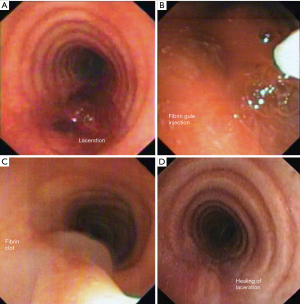

After completing local anaesthesia of the throat and the vocal folds, the patient is placed in supine position and moderate sedation is started; a plastic mouthpiece is inserted to protect the instrument from an inadvertent bite; the face mask is positioned on the patient’s face, ensuring an adequate seal; the flexible bronchoscopy is inserted through the face mask, passes the epiglottis and then is inserted through the vocal folds into the trachea. After identification of tracheal laceration, the double lumen catheter is inserted through the working channel of the bronchoscopy; the distal tip of catheter is placed close to the tracheal laceration; and the two components of fibrin glue are instilled simultaneously into the tracheal laceration. After mixing both components, polymerization of fibrin occurs resulting in an elastic and opaque clot that closes the lesion. Finally, the bronchoscopy is extracted. Two examples are reported in Figures 3-6.

In our experience, this procedure was applied in six patients with PITL in the last two years (Table 1). As fibrin glue is an approved medical device routinely used in clinical practice also for closure of tracheal laceration (11), a specific ethical approval was not required. All patients were informed of the risks and benefits of the procedure and give a signed permission to perform it; in addition, they were aware that their data could be used anonymously for scientific purpose only.

Full table

The median age of population was 72 (range, 57–77) years old; all patients were female but one. In all cases, an elective intubation with a single-lumen endotracheal tube was performed. The PITL was diagnosed in the early post-operative hours [median 8 hours (range, 5–37 hours)]. Subcutaneous emphysema was present in all cases and associated with haemoptysis in 3 cases. The median length of lesion was 3.5 cm (range, 3–5 cm) involving the mucosa (n=1), the sub-mucosa (n=2), and muscularis mucosa (n=3). The lesion was localized in the upper trachea (n=3); mid trachea (n=2); and between the carina and main right bronchus (n=1). All patients but one had spontaneous breathing. Endoscopic treatment closed with success the PITL in all cases but one who required a surgical repair through right thoracotomy. No recurrence was found [median follow-up: 17 (range, 8–21) months].

Roles of team members

Figure 7 summarized the position of the team members as following:

- The operator is positioned behind the head of the patient and the monitor is placed in front of him on the left or right side;

- The assistant stays near the operator, on the right or left side, introducing through the working channel of the bronchoscopy the appropriate endoscopic materials;

- The nurse stands on the side opposite the monitor, passing appropriate endoscopic materials to the assistant;

- The anaesthetist sits cranial to the patient; he assures a moderate sedation and spontaneous ventilation; and monitories all cardio-respiratory parameters as the blood pressure, oxyhemoglobin saturation, and tidal volume.

Postoperative management

Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy against the trachea-bronchial flora, antiseptic anti-inflammatory aerosol therapy, antitussive medication, and total parenteral nutrition are provided for at least one week and/or until bronchoscopic confirmation of tracheal laceration healing. Follow-up endoscopic controls are performed 1, 3 and 6 months later.

Tips and tricks

A duploject plunger was used to inject the two compounds through the catheter simultaneously, while the patient was not being ventilated for 60 sec. A duploject plunger was used to inject the two compounds through the catheter simultaneously, while the patient was not being ventilated for 60 sec.

- A disposable cap should seal the cylinder of the face mask through that the bronchoscopy is inserted to prevent air leakage during the procedure and patient’s desaturation.

- Since the two components of fibrin glue have different viscosities, the assistant should inject simultaneously them to avoid that a premature clotting can occlude the double lumen catheter.

- The tip of the catheter should be at a sufficient distance from the bronchoscope during the injection of fibrin glue to prevent any damage to the working channel and/or the optics of the bronchoscope (15).

- After the closure of the tracheal laceration by clot, it is important to avoid any contact with the tip of the catheter and/or of the bronchoscopy. In addition, no bronchoscopic suction should be applied in this area to prevent the aspiration or misplacement of the clot.

- In case of patient under mechanical ventilation, the tip and the cuff of endotracheal tube should be placed distal to the rupture.

Conclusions

Endoscopic management with instillation of fibrin glue is an easy and feasible strategy that supplements medical treatment of PITL. The tissue glue covers the tracheal laceration and promotes tissue sealing and regeneration. However, the key success of the procedure is the accurate selection of patients. This strategy is indicated in clinically stable patients and in spontaneous respiration, having superficial lesion (≤4 cm in length and without oesophagus injury) localized in the upper or middle trachea and without clinical and radiological signs of mediastinal collection, of emphysema and/or pneumomediastinum progression, and of infection. The presence of mechanical ventilation is not a major contraindication for endoscopic repair but the tip of the endotracheal tube should be placed distal to the rupture (bridging the lesion). When the lesion is located in close proximity to carina or involves the carina and the origin of the main bronchus, as occurred in our patient 4, the treatment of choice remains surgery because separate endobronchial intubation may not be successful (11). PITL >4 cm and involving muscularis or oesophageal mucosa could also be reviewed for endoscopic closure with fibrin glue if the patient is unfit for surgery. However, in this case the procedure is associated with a high rate of failure.

Limitations of the study are the retrospective nature, the small number of patients and the lack of a control group. The decisional algorithm for closing the tracheal laceration with fibrin glue was based on the morphological characteristics of the lesion and on patient’s clinical condition. We did not collect data on all patients with PITL but only on those undergoing endoscopic management with fibrin glue. Thus, without a control group, it is not conclusive that the healing of tracheal laceration is directly related to the placement of fibrin glue. In theory, the cases that healed with fibrin glue would have healed on their own. Thus, all these limitations cannot allow to propose a specific protocol for the endoscopic management with fibrin glue of PITL that should be validated by future prospective larger studies.

Acknowledgements

Alfonso Fiorelli thanks Tecla Della Posta and Diana Mancino for helping him during the procedures.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Miñambres E, Burón J, Ballesteros MA, et al. Tracheal rupture after endotracheal intubation: a literature systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35:1056-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carbognani P, Bobbio A, Cattelani L, et al. Management of postintubation membranous tracheal rupture. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:406-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen JD, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, et al. Using CT to diagnose tracheal rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:1273-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fiorelli A, Petrillo M, Vicidomini G, et al. Quantitative assessment of emphysematous parenchyma using multidetector-row computed tomography in patients scheduled for endobronchial treatment with one-way valves†. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19:246-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mullan GP, Georgalas C, Arora A, et al. Conservative management of a major post-intubation tracheal injury and review of current management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007;264:685-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider T, Storz K, Dienemann H, et al. Management of iatrogenic tracheobronchial injuries: a retrospective analysis of 29 cases. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1960-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Caro A, Ausín P, Moradiellos FJ, et al. Role of conservative medical management of tracheobronchial injuries. J Trauma 2006;61:1426-34; discussion 1434-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fong PA, Seder CW, Chmielewski GW, et al. Nonoperative management of postintubation tracheal injuries. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:1265-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Arrigo E, et al. Management of subtotal tracheal section with esophageal perforation: a catastrophic complication of tracheostomy. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E337-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conti M, Porte H, Wurtz A. Conservative management of postintubation tracheobronchial ruptures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:821-2; author reply 822. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jougon J, Ballester M, Choukroun E, et al. Conservative treatment for postintubation tracheobronchial rupture. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:216-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardillo G, Carbone L, Carleo F, et al. Tracheal lacerations after endotracheal intubation: a proposed morphological classification to guide non-surgical treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:581-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fiorelli A, Cascone R, Di Natale D, et al. Video 1 edited the main steps for closing a 3 cm tracheal fistula in a 57-year old woman after elective single-lumen endotracheal intubation for breast surgery. Asvide 2017;4:320. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1632

- Fiorelli A, Cascone R, Di Natale D, et al. Video 2 edited the main steps for closing a 3 cm tracheal fistula in a 71-year old man after elective single-lumen endotracheal intubation for lumbar disc surgery. Asvide 2017;4:321. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1633

- Fiorelli A, Frongillo E, Santini M. Bronchopleural fistula closed with cellulose patch and fibrin glue. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2015;23:880-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Fiorelli A, Cascone R, Di Natale D, Pierdiluca M, Mastromarino R, Natale G, De Ruberto E, Messina G, Vicidomini G, Santini M. Endoscopic treatment with fibrin glue of post-intubation tracheal laceration. J Vis Surg 2017;3:102.