Aortic valve sparing aortic root replacement (David procedure) via an upper hemisternotomy: Hannover experience

Introduction

In recent years, minimally access cardiac surgery has gained broader clinical application due to potential benefits of reduced surgical trauma and pain (1,2).

For many years, the ‘Gold Standard’ for the treatment of a combined pathology of the ascending aorta and the aortic valve was the composite replacement with a valved conduit, as first described by Bentall and De Bono (3). In recent years, in patients with normal aortic valve leaflets, aortic valve-sparing aortic root operations such as the re-implantation (David) procedure have become popular (4-9).

Valve-sparing aortic root replacements are technically more complex and demand a high level of surgical skill. Due to this reason, minimally access valve sparing aortic root replacements have not been performed routinely.

During the past decade, we have routinely performed minimally access David procedures (10).

The purpose of this manuscript was to present our technique and results (Video 1).

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study is waived from ethical approval by the ethics committee or institute review board. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the filming and publication for the surgical video.

Patient selection

After more than 500 David procedures via full sternotomy had been performed at our center, we started minimally access ‘David procedure’ in carefully selected elective patients. Initially, relatively young patients (<60 years) with isolated aortic root aneurysms and aortic valve insufficiency without leaflet calcification, and no significant co-morbidities were selected. After initial excellent results, we started performing all elective isolated David procedures through this access.

The pre-operative data are given in Table 1.

Table 1

| Total patients (n) | Number (n=62) |

|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 55 (88.7) |

| Age (years) | 48.5±12.1 |

| Known Marfan syndrome, n (%) | 6 (9.7) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 5 (8.1) |

| COPD, n (%) | 2 (3.2) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve, n (%) | 24 (38.7) |

| Aortic valve insufficiency (echocardiography), n (%) | |

| ≤1° | 15 (24.2) |

| ≤2° | 15 (24.2) |

| ≤3° | 29 (46.8) |

| ≤4° | 3 (4.8) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Pre-operatively, in addition to routine clinical examinations, coronary angiography (in patients above 40 years of age), echocardiography and computer tomography scans were performed. A minimally access David procedure was considered if the pre-operative echocardiography showed normal aortic valve leaflets, free of calcification and the level of the aortic root was not lower than 5th intercostal space in pre-operative X-ray. The final decision to proceed with a valve-sparing operation was taken by the surgeon intra-operatively, after inspection of the aortic valve.

The David procedure was performed with a Valsalva graft in 16 (26%) patients while a straight tube graft (David I) was used in 46 (74%) patients.

Surgical technique

In addition to the standard protocol for sternotomy cases, external defibrillator pads are placed. One groin and leg are always prepared to allow for easy femoral and saphenous vein access if needed.

The ascending aorta and the aortic root are exposed via an upper J mini-sternotomy (up to the 3rd or the 4th intercostal space).

After systemic heparinization, the ascending aorta and the right atrium are cannulated directly via the hemi-sternotomy access. If the ascending aorta is extremely dilated blocking the access or the right atrium is too deep, it may be easier to cannulate the superior Vena Cava and push the cannula into the inferior Vena Cava to initiate cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Alternatively, venous access can be performed via the femoral vein. Depending upon the extent of surgery, the patient is cooled either to 32 ℃ in isolated David procedures or lower in case of additional aortic arch surgery.

A mediastinal chest tube and temporary epicardial pacing wires are placed via a small sub-xiphoidal incision. A CO2 sufflation line is placed in the pericardium. After fibrillating the heart, a vent is inserted into the left atrium via the upper right pulmonary vein.

The aorta is cross-clamped and opened. Cold blood cardioplegia (Buckberg) is our preferred method of myocardial protection during David procedures. Cardioplegia is repeated every 30 minutes.

The ascending aorta is transected slightly above the commissures and the aortic valve is assessed. The aortic root is mobilized from outside to a level below the level of the aortic annulus. Small vessels are meticulously cauterized during aortic root mobilization. Meticulous care is taken to ensure perfect hemostasis at every step of the operation.

Open in a separate window

The aortic sinuses are resected to leave a rim of approximately 5 mm of the aortic wall and the coronary ostia are excised as buttons. If necessary, leaflet plasty is performed with 7-0 Prolene to optimize the cusp coaptation.

Open in a separate window

The diameter of the aortic annulus is determined with a Hegar’s dilator. The diameter of the prosthesis is then calculated. The diameter of the Hegar’s dilator +2 sizes bigger determines graft diameter. In most of the patients however, the diameter of the Dacron prosthesis is either 28 or 30 mm.

Thereafter, 12 unpledged threads of 2-0 coated polyester fiber (Ethibond, Ethicon Inc., USA) are placed, inside-out and horizontally, below the valve in a circumferential fashion. The Dacron graft or Valsalva graft (Vascutek Inc., Glasgow, Scotland) is anchored with the aortic root inside the graft. The Dacron graft is fixed by tying these threads loosely to avoid the creation of a subvalvular stenosis.

Open in a separate window

If a straight tube graft is being used, the commissures are pulled-up maximally without stretching the Dacron graft and then fixed to the Dacron graft. If a Valsalva graft is used, the commissures are reimplanted at the level of the ‘neo ST junction’. The mobilised aortic root with remnants of the aortic sinuses are sutured to the inside of the Dacron graft using three 4-0 polypropylene sutures (Prolene, Ethicon Inc., USA). This is the ‘hemostatic’ suture-line and as such, has to be absolutely ‘blood-tight’.

A ‘water-test’ is performed to test the coaptation of the reimplanted aortic valve. If necessary, additional aortic valve leaflet plasty is performed.

Open in a separate window

The coronary ostia are reimplanted to the Dacron graft after creating small ‘neo Ostia’ with 5-0 polypropylene suture (Prolene, Ethicon Inc.). Hemostasis of the coronary anastomoses and performance of the aortic valve is tested by pressurizing the aortic root with cardioplegia.

The distal aortic anastomosis is then performed. After meticulous ‘de-airing’ of the left ventricle, the aortic clamp is removed.

The surgical result is assessed by transoesophageal echocardiography. After weaning the patient from CPB, meticulous hemostasis is performed before closing the chest.

Transthoracic echocardiography is again performed before discharge. Patients are anticoagulated with coumadin or aspirin (at the discretion of the individual surgeon) to prevent thromboembolic complications for two months. Thereafter, anticoagulation therapy is discontinued unless other indications exist.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed with SPSS 21.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Numbers are given as total and relative number.

Results

There were no intra-operative conversions to full sternotomy. The intra-operative data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Intra-operative data | Number (n=62) |

|---|---|

| Aortic x-clamp time (minutes) | 126.4±28.8 |

| CPB time (minutes) | 191.4±39.0 |

| Mean hypothermic circulatory arrest time (min)* | 1.3±4.8 |

| Selective antegrade cerebral perfusion time (min)# | 0.4±2.2 |

| Operation time (min) | 292.5±59.1 |

| Concomitant procedures, n (%) | |

| Prox. aortic arch replacement | 5 (8.1) |

| Aortic valve leaflet plasty | 30 (48.4) |

| CABG | 2 (3.2) |

| ASD-closure | 2 (3.2) |

| VSD-closure | 1 (1.6) |

| Intra-op blood products: | |

| Packed RBC (U) | 0.8±1.6 |

| Platelets (U) | 1.1±1.2 |

| FFP (U)& | 0.9±1.9 |

| Post repair echocardiography, n (%) | |

| ≤1° | 61 (98.4) |

| ≤2° | 1 (1.6) |

*, 5 patients; #, 2 patients; &, 25 patients without blood products. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ASD, atrial septal defec; VSD, ventriculoseptal defect; RBC, red blood cell; FFP, fresh frozen plasma.

Open in a separate window

There were no deaths within the 30-day postoperative period (30 POD). The post-operative data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Post-operative data | Number (n=62) |

|---|---|

| Mech. ventilation time (days) | 0.6±1.0 |

| ICU stay (days) | 1.8±1.4 |

| Rethoracotomy for bleeding, n (%) | 5 (8.1) |

| Conversion to full sternotomy | |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1 (1.6) |

| Resp. Insuff. needing tracheostoma | 0 |

| Acute renal failure, Temp. dialysis, n (%) | 1 (1.6) |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 1 (1.6) |

In follow-up echocardiography (477.2±321.1 days), 57.7% (n=15) patients had aortic valve insufficiency either 0° or minimal. Another 26.9% (n=7) had aortic valve insufficiency 1°. Only 15.4% (n=4) patients had aortic valve insufficiency grade 1–2.

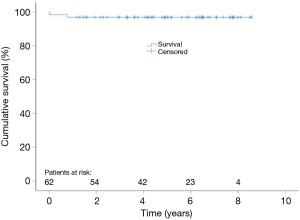

Follow up data is given in Table 4. Figure 1 shows Kaplan Meier estimates of survival.

Table 4

| Follow-up data | Number (n=62) |

|---|---|

| Survival (days) | 1471.1±840.3 |

| Re-do procedure, n (%) | 4 (6.5) |

| Prosthetic graft infection | 1 |

| Early AR | 2 |

| Late AR | 1 |

| Time to re-do procedure | 205.3±254.9 |

AR, aortic regurgitation.

Discussion

Several studies have shown that minimally access aortic valve replacement (AVR) patients have better post-operative results in terms of hospital stay, post-operative pain, duration of ventilation and blood loss compared to full sternotomy patients (1,2). Avoiding a full sternotomy should also contribute to improved postoperative stability of the sternum and consequently quicker rehabilitation. This can be important in older patients. On the downside, limited exposure of the operative field makes the technically complex David procedure even more challenging.

The ‘Bentall’ operation has been seen as the ‘gold standard’ for the treatment of combined pathology of the ascending aorta and the aortic valve (3). Since first proposed three decades ago, the aortic valve-sparing re-implantation procedure (David) has established itself as an alternative in patients with normal aortic valve (4). However, due to its complexity, David procedure has not been done routinely via a minimally access technique.

In our experience, meticulous attention to hemostasis is a critical factor during minimal invasive access David procedures.

Conversion to full sternotomy was not required in this series. In addition, the 30-day mortality was very low. One (1.2%) patient died due to fat embolization into the left coronary artery on the first postoperative day.

We used both the David I technique with a straight Dacron graft as well as a Valsalva Dacron graft. We did not find any difference between these grafts in terms post-operative valve insufficiency. Careful patient selection for this approach should be considered.

At present, the contraindications for minimally access David procedure are:

- ‘Re-do’ operations and those needing concomitant cardiac procedures, such as coronary bypass operation and mitral valve operations.

- A very deep aortic root.

In view of the fact that most the patients with a connective tissue disorder (e.g., Marfan syndrome) or those with bicuspid aortic valves present at a relative young age, it is important for the surgeons to be able to offer minimally access surgery as cosmesis is an important factor for these patients.

In the elderly patients, the possibility of shorter convalescence period is the main advantage of minimally access surgery.

Conclusions

Our experience shows the feasibility and safety of minimally access David procedure in carefully selected patients. Combining the advantages of minimally access along with that of valve sparing surgery allows the patients to return to their normal lives earlier.

Therefore, at our center, minimally access David procedure has become the standard access in all elective patients coming for isolated David procedures.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Filip Casselman and Johan van der Merwe) for the series “Aortic and Mitral Valve Innovative Surgery” published in Journal of Visualized Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jovs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jovs-2019-19/coif). The series “Aortic and Mitral Valve Innovative Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was in line with our institution’s ethical standards. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the filming and publication for the surgical video. This study is waived from ethical approval by the ethics committee or institute review board.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mihaljevic T, Cohn LH, Unic D, et al. One thousand minimally invasive valve operations: early and late results. Ann Surg 2004;240:529-34; discussion 534. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakir I, Casselman FP, Wellens F, et al. Minimally invasive versus standard approach aortic valve replacement: a study in 506 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:1599-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bentall H, De Bono A. A technique for complete replacement of the ascending aorta. Thorax 1968;23:338-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- David TE, Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;103:617-21; discussion 622. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pethig K, Milz A, Hagl C, et al. Aortic valve reimplantation in ascending aortic aneurysm: risk factors for early valve failure. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:29-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shrestha M, Baraki H, Maeding I, et al. Long-term results after aortic valve-sparing operation (David I). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:56-61; discussion 61-2. [PubMed]

- Shrestha ML, Beckmann E, Abd Alhadi F, et al. Elective David I Procedure Has Excellent Long-Term Results: 20-Year Single-Center Experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;105:731-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martens A, Beckmann E, Kaufeld T, et al. Valve-sparing aortic root replacement (David I procedure) in Marfan disease: single-centre 20-year experience in more than 100 patients†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;55:476-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beckmann E, Martens A, Krueger H, et al. Aortic Valve-Sparing Root Replacement (David I Procedure) in Adolescents: Long-Term Outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shrestha M, Krueger H, Umminger J, et al. Minimally invasive valve sparing aortic root replacement (David procedure) is safe. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2015;4:148-53. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Beckmann E, Martens A, Krueger H, Kaufeld T, Haverich A, Shrestha M. Aortic valve sparing aortic root replacement (David procedure) via an upper hemisternotomy: Hannover experience. J Vis Surg 2021;7:3.